AS Graanul Invest

Humala str. 2, 10617 Tallinn, ESTONIA

Humala str. 2, 10617 Tallinn, ESTONIA

The Profundo report, published in June 2021 and commissioned by Greenpeace, analyses whether the rapidly growing biomass demand of the Dutch market is driving increased logging or negative impacts on natural forests in the Baltic countries, with a focus on Estonia. The report is based on two NGO studies conducted by the Estonian Fund for Nature (ELF) in collaboration with the Latvian Ornithological Society (December 2020) and Estwatch (March 2021). Unfortunately, the published information ignores important viewpoints of expert groups, academia and government data and therefore doesn´t give objective overview of the situation.

According to Estonian Environmental Ministry, Estonian forest land is increasing and the total growing stock, growing stock per hectare, as well as the annual increment have been increasing gradually. In Estonia the total share of protected forests is high (25%), and the share of strictly protected forests (no management) is also high (ca 14%). During last 5 years, the overall protected area has increased ca 50 000 hectares, mostly for forest protection. Moreover, the use of the lowest quality wood for bioenergy does not affect forest management practices, and forests are not felled due to the demand for wood pellets. The use of wood residues for energy is a natural part of the circular economy of the forest and wood industry. The below outlines this.

The Baltic countries have managed to establish a fair balance between preserved nature, sustainable forest management and highly developed forest-based industries. The management of our forests has not been consistent due to historical reasons (due to Soviet occupation) and that influences the state of the forests as well as the choices we have today. Forest land area has increased during the last 70 years about 1.5 times. The total growing stock, growing stock per hectare, as well as the annual increment have been increasing gradually.

According to Estonian ministry of Environment, Estonian felling volume has been smaller than the increase of growing stock. For example, in the period 2011-2019 the average felling volume was 10,7 mln m3 and the average annual increment was 16,2 mln m3. Forest growing stock has raised gradually due to both increase in forest land area as well as its average age. Taking into account the age structure and species composition, land-use history, growth models and future projections, the timely and appropriate renewal of our managed forests is extremely important for both sustainable land use and long-term climate targets.

In Estonia, forests are being cut in order to use the material in the timber and plywood industry. As the cutting volumes of forestry increase, the amount of residual material remaining from the sector also increases, and the residues of the timber and forest industry move to heat and energy production. All actors in the field already acknowledge the importance of sustainable forest management as a precondition for biomass harvests. This includes, for example, protection of highly biodiverse areas, management that ensures regeneration after harvest, and maintenance of productive capacity – meaning that the managed forest continues to convert atmospheric CO2 into wood.

There is absolutely no uncertainty about how much wood is used of energy and non-energy industries and the proportion is very similar to the returns of energy grade wood from normal forestry.

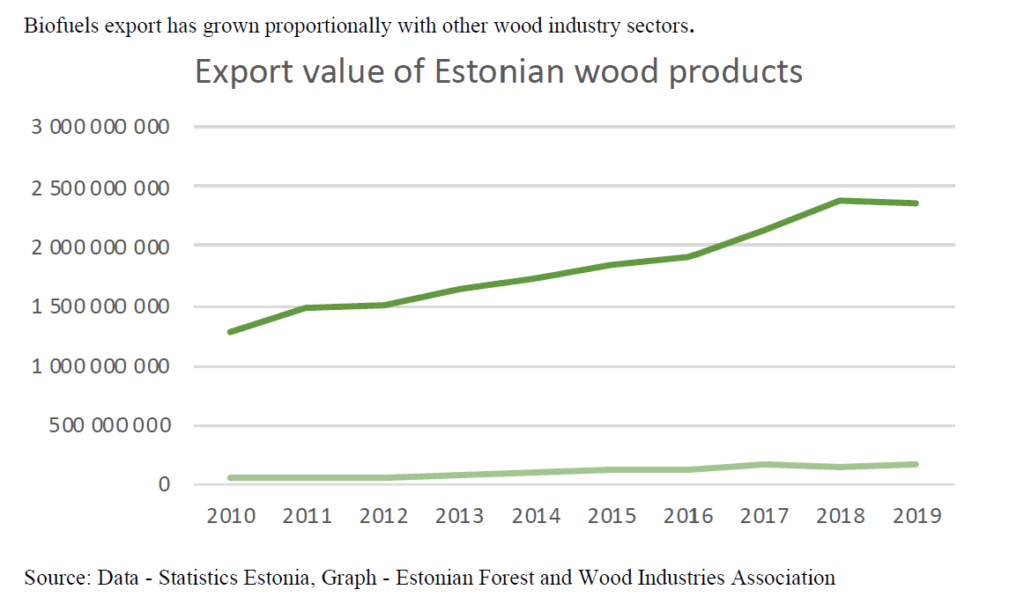

Roughly 70% of energy wood, forest chips and wood industry residues are used locally in Estonia to heat houses, industries and cities in Estonia and only the surplus 30% is exported as pellets or heat chips to other countries.

According to Estonian ministry of Environment in Estonia all Natura 2000 areas are protected through nationally protected areas. By Nature Conservation Act nationally protected areas are divided to different protection zones: strict nature reserve, conservation zone and limited management zone. In the first two human intervention is either completely prohibited or at least economic activities are prohibited (including forest management); in the third zones economic activities are allowed, but limited.

The main purpose of limited management zones is to be a buffer zone between strictly protected areas and conventionally managed forests. Therefore, the economic activities are allowed in limited manner so they will not compromise set conservation aims. In case of forest management, there are additional restrictions compared to the criteria set in the Forest Act, for example stringent limitations to the size of cutting areas, time of cutting or form of cutting, criteria for age composition or increased amount of retention trees. According to Nature conservation Act by establishing the protection regime of the Natura 2000 areas the ecological needs of habitat or species must be followed. Impact of possible felling activities are considered during the process of establishing the protection rules and before approval of each felling permit. This stipulates that that the conservation goals are achieved and the economic activities are allowed only to the extent that will not harm those goals.

Big parts of forest fellings in protected areas have been carried out in those areas where no Habitat’s Directive habitats are found, and the cutting has been necessary to achieve a conservation aim (i.e. restoration of mires or semi-natural grasslands). On 2009-2018 approximately 60 000 ha. of forest has got felling permissions in Natura areas, that includes also felling to meet conservation objectives. Also note that the permit does not obligate to conduct the felling. In addition, if felling is not conducted, the felling permit may be issued for the same area several times. Therefore, the actual felling area is smaller than felling permits show.

To ensure that conservation aims are achieved and not compromised by economic activities, the protected areas are analyzed by Environmental Agency using holistic approach, including set forest management criteria. When necessary, i.e. the conservation value has increased and/or there is a need for more stringent regulation to achieve conservation goals, management criteria are strengthened or selected areas are re-zonated to strictly protected zone. Please note, that during last 5 years, more than 75 000 ha different (mostly forest) habitats have been transferred to more strictly protected conservation zone.

The amount of protected forest area in Estonia has increased in time. According to NFI1 the total share of protected forests is high (25%), and the share of strictly protected forests (no management) is also high (ca 14%). During last 5 years, the overall protected area has increased ca 50 000 hectares, mostly for forest protection.

Forestry company Valga Puu follows all requirements of the law as well as international best management practices, including the extensive requirements of most recognized certification systems. Valga Puu has managed some areas in the Nature 2000 for a long time now and there have been no shifts in their management practices. Valgu Puu’s ownership in Haanja has grown at the same rate as the company’s overall forest portfolio.

In 2020 Graanul Mets forestry companies have carried out the following works on 83,2 hectares in Haanja Nature Park: 8,5 hectares of cutting, 10,6 hectares of cutting with the aim of removal of dead and/or sick trees (called sanitary cutting) and 0,6 hectares thinning. 37,7 ha of planting and 25,8 ha of maintenance of young trees.

The use of the lowest quality wood in bioenergy does not affect forest management practices and forests are not felled due to the demand for wood pellets. The use of wood residues for energy is a natural part of the circular economy of the forest and wood industry.

In Estonia, forests are being cut in order to use the material in the timber and plywood industry. As the cutting volumes of forestry increase, the amount of residual material remaining from the sector also increases, and the residues of the timber and forest industry move to heat and energy production. All actors in the field already acknowledge the importance of sustainable forest management as a precondition for biomass harvests. This includes, for example, protection of highly biodiverse areas, management that ensures regeneration after harvest, and maintenance of productive capacity – meaning that the managed forest continues to convert atmospheric CO2 into wood.

Indufor, the world’s leading provider of advisory services on forest and natural resources, has produced a comprehensive report in 2020 on the impact of demand for wood-based bioenergy, which shows that bioenergy does not affect forest management practices and cutting volumes.